THE COMMEDIA MUST GO ON

Welcome.

VIRTUAL PROLOGUE BY THE AUTHOR

Smorfia: Prologue, 61

Dicette Pullecenella:

‘A ccà me trase e pe’ culo m’esce

al Libro Cartaceo

VITA MORTE E RESURREZIONE DI

PULCINELLA

The Character Who Kept the Commedia dell’Arte Alive

di Antonio Fava

In the hardcopy version of my PULCINELLA, the patient reader will notice some insistence on a few concepts. There are two reasons for this. The first one comes from my teaching experience, in which I learned the importance of continuously repeating fundamental concepts and principles. The second is the direct consequence of the sometimes adventurous creative process of writing the book in different times and spaces, including non-traditional spaces such as airports and airplanes, trains, train-stations, hotels, and wherever I was walking by myself. In short, I took advantage of all those very precious, irreplaceable moments and spaces fundamental to writing a book, since 90% of my waking time is spent in social activities. For this reason, when I started to reread my notes, I noticed certain issues of repetition. I resolved most of them, but I didn’t want to resolve them all.

Continue reading...

Anyone directly involved in theater, wherever it is performed and however it is disseminated, never does – or at least, never does everything – that the theater historians and critics claim they do. To be more precise, the theater historians and critics are never able to explain, no matter how hard they try, what the actors actually do on the stage and how they do what they do: In which way and for what real and precise reasons the actors do what they do. The historians’ and critics’ explanations are always disconcertingly abstract, abstruse, and inapplicable. They are terrible observers. They watch and they definitely see something, but they see something other than what we really do and create; and if – after reading the critique of our work – we were to try to repeat on stage what we previously did, but according to the description given by one of these observers, we would not be able to do it again. We would not be capable of it. When actors read critical reviews of their acting or of the performance they are part of, they

Nearly all of the written documentation, both critical and testimonial, on Commedia dell’Arte is deprecating. And it is sincere in this sense. Nowadays, we can obtain a lot of information about Commedia from those disparaging comments, expressions of disgust that the art form provoked. We can even reach better understanding of Commedia through those negative comments than through praise. This is because the negative comments, besides being more frequent, are more detailed, sincere in their own way, and to the point. Here is what Tommaso Garzoni writes in “Piazza Universale” on pages 739 and 740: “The minute the Comics enter a city, immediately the drums announce their arrival. The Signora, dressed as a man and with a sword in her hand, passes them in review. They invite people to go and see a comedy, a tragedy or a pastoral in the palace or at the Pilgrim’s tavern. Eager for novelty, the curious commoners hasten to fill the room. Having paid admission, they enter the room that has been fitted with a provisional stage, with artless scenery drawn with charcoal. You can hear an overture played by donkeys and hornets; a prologue from barkers, an awkward tone as that of Fra Stoppino; acts as unpleasant as an illness; interludes worth a thousand gallows; a Magnifico who is completely worthless, a zanni who looks like a goose; a Graziano who shits out words, a vapid and silly procuress, a lover who cripples everyone’s arms when he speaks, a Spaniard who can’t say anything other than ’mi vida,’ ’mi corazon’; a Pedant who falls into Tuscan words at every turn, a Burattino whose only gesture is that of putting on his hat, a Signora who is coarse in saying, dead in speaking, asleep in gesturing, who has made the graces her perpetual enemies and keeps a capital disagreement with beauty.3”

Someone has to do the critique of the critique. It is not the purpose of this book, even though, as an actor, it is hard for me to refrain from it. If I try to do it, it is not to protect or defend myself (I am doing well, really well: my health is good, touch wood, and I am fine professionally) but it is to offer my contribution (at least I try) to protect the actors, specifically those who act in the spirit of the Tradition. When modern historiographers of the Art got into their heads that Commedia is only one character, Arlecchino5, who is (they say) a devil, inferring that Commedia is hellish, diabolical, they not only talked nonsense, but also, from their high academic authority spread monstrous and deliberate misinformation that has stuck. Unfortunately, we can’t now shake this impression off. If Commedia really were what those “analyses” describe, we wouldn’t know what to do with the stories of its characters, which are (so) normal, urbane, secular, and down to earth. This is how it is in the comic repertoire (70% of the Commedia’s plays), in the fantastical and magical repertoire and also in the grim and gruesome tragedies. In the small – proportionally – quantity of magicians, magic, executions, appearances of supernatural beings, and hells of every kind there are always the normal, secular, and down to earth comic types. They are invariably present, always at the center, always indispensable: Old men lusting after young sweet things; Servants with their irresolvable survival needs; Lovers with their pangs of love; Captains with their arrogance. They are always there to remind us that they are the ones who

During the Romantic period, when Commedia dell’Arte disappeared, Pulcinella remained, keeping it alive. Pulcinella, who was only a part of Commedia dell’Arte, succeeded in regenerating it and rebuilding it as a whole.

My contributing effort will continue, soon after this work on Pulcinella, with even more material for reflection, explanation, and demonstration. I don’t have a title in mind yet for my next publication, on which I am already working. It will develop, amplify, update, and enrich the first one. One thing is certain, quite certain, for me and for those who think like me: The current explosion (which seems an implosion, since it is confined to social networks, unleashed on the streets from time to time, but definitely absent from theaters) of a certain would-be Commedia, superficial, formless or a mix of forms, quickly diffused, seems to verify the hyper scientific historiography and critique.

Antonio Puricinedda Fava

Reggio Emilia, Italy, January-February 2014

Notes: 1. Pulcinella said: “Here, it goes into the mouth and goes out from the butt” 2. Life, Death and Resurrection of Pulcinella. 3. Tommaso Garzoni, La piazza universale di tutte le professioni del mondo, Venice, 1589. 4. Gnoccaggine (dumbness), facility, ease. Gnocco 1: Typical bread flavored with ciccioli [food prepared from pig fat: translator’s note] the region of Reggio. Gnocca 1: Simpleton, silly person. Naïve. Gnocca 2: A beautiful and desirable woman. 5. Arlecchino is one of the many names for zanni II in Commedia dell’Arte. He is not a unique character, but he is one variation, among the others, of one specific comic type in Commedia dell’Arte. It is typical in Commedia to have many names for the few comic types. The Old man can be Magnifico or Dottore; the Servant has two variants: First and Second, Clever and Foolish; the Lovers come in pairs, multiple pairs in many plays; the Captain. There is nothing else. Other characters are only momentary, useful for a precise action or in a certain specific comedy. For this reason, they cannot be counted in the privileged group of the “set types” or indispensable characters. However, even if the set types are just a few, their names are countless. Why? For the obvious reason that if on the one hand there is the actor who continues the family tradition or the Maestro of great fame, on the other hand there are the majority of the actors who invent their names and their maschema [typical details of a character]. They remain in the Tradition, but with a personal touch. Arlecchino is only one of the many names given to the foolish servant. Also, let’s add that many zanni II, with different names, look identical, with the same colorful patched costume (later with elegant diamond shapes), the same cap, the same dark face, generally with a flat nose. The myth was born at the table, better yet, at the writing-desk: The first theories about the mask-devil appear in the 1950s. Everyone talks about the mask-devil as if it were real. However, no one will cast it as a character on stage because it is simply alien to the genre and thus not usable. The only concrete and disgraceful effect that comes from it is the ‘protagonism’, in that variation that is literally infesting: Commedia, ladies and gentlemen, doesn’t have ONE protagonist, for the simple reason that all the characters are protagonists. The Companies of the Art created a system in which all the specialists, the maestri were equal. There were only two requirements for everybody: to be good actors and make the audience happy. 6. In Italian “pollo” (chicken) means simpleton. [translator’s note]. 7. Among the actors who have succeeded in explaining what they do: Massimo Troiano, Discorsi delli triomfi, apparati e delle cose più notabili, fatte nelle sontuose nozze dell’Illustrissimo et Eccellentissimo signor duca Guglielmo, primo genito del generosissimo Alberto Quinto, conte palatino del Reno e duca della Baviera alta e bassa, nell’anno 1568, a’ 22 di febraro, by Massimo Troiano from Naples, Musician of the Illustious and Most Excellent Duke of Bavaria. In Monaco, published by Adamo Montano, MDLXVIII. Flaminio Scala, Prologo della comedia del Finto Marito, in Venice, published by Andrea Baba, 1618 (1619); Il Teatro delle Favole Rappresentative, overo La Ricreatione Comica, Boscareccia, e Tragica: divisa in cinquanta giornate. In Venice, published by Gio:Battista Pulciani. MCDXI. Pier Maria Cecchini, nobleman from Ferrara, known as Frittellino among the comedians, Frutti delle moderne comedie et avisi a chi le recita, Padua, 1628. Nicolò Barbieri, La Supplica Discorso Famigliare di Nicolò Barbieri detto Beltrame diretta a quelli che scrivendo ò parlando trattano de Comici trascurando i meriti delle azzioni virtuose. Lettura per quei galantuomini che non sono in tutto critici, ne affatto balordi. In Venezia con licenza de’ Superiori e Privilegio per Marco Ginammi Lanno MDCXXXIV. Luigi Riccoboni, Histoire du Théâtre Italien, A Paris, De l’Imprimerie de PIERRE DELORMEL, 1728. Antonio Piazza, Il Teatro ovvero fatti di una Veneziana che lo fanno conoscere, in Venice 1777. Le mime Séverin, L’Homme Blanc, souvenir d’un Pierrot, Plon, Paris, 1929. Dario Fo, Manuale minimo dell’attore, Giulio Einaudi Editore, Turin, 1987. Antonio Fava, La Maschera Comica … cit. Maschera & Maschere, exhibition catalog. Les masque Comiques d’Antonio Fava, par THEATRUM COMICUM, Geneva, 2010. Vita Morte e Resurrezione di Pulcinella, ArscomicA, Reggio Emilia, 2014. Along with other, more important names. In any case, this is still a small sampling of from an extensive number of actors. 8. I adore the verb “fare” [which in English can mean both “to do” and “to make”: translator’s note]

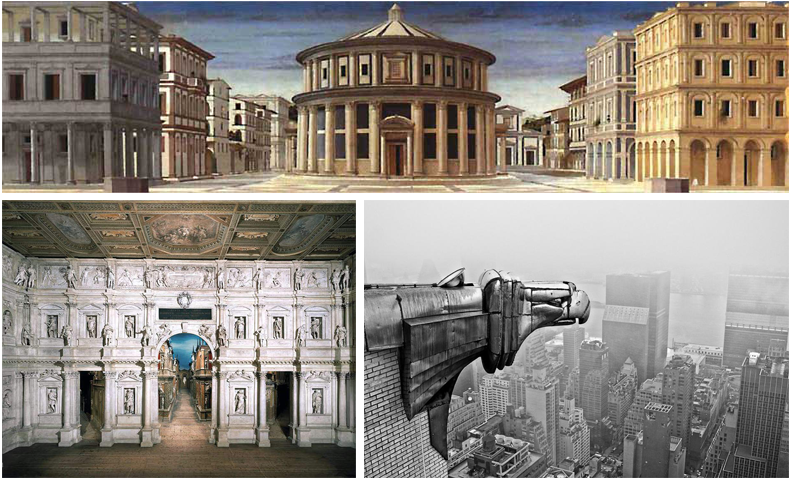

This term refer to the historical period between the thirteenth and the eighteenth centuries; however, Renaissance is more commonly understood as the time between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when ’modernity’ began: as a school of thought, as a research method, as a vision of the world.

At the end of the fifteen century, along with the humanist movement of that period, we see the beginning of modern theatre (Humanist Comedy), followed by Professionalism in the thirties of the sixteenth century: Commedia dell’Arte was born.

Well, this is the key perspective to this world, this culture, through the theatrical disciplines born in that period, which are offered, researched, taught and produced today: that of a long, very Long Renaissance.

Personally, I do believe that Renaissance is still alive.

Today’s theatrical culture has a tendency to split into ’genres’ what, during the Renaissance, was the compulsory combination of essential components: even the crudest realism had to imply a touch of ’absurdity’; my aim is to combine once again what has been conceptually split, with the pleasure and wisdom we inherit from that extraordinary period.

Commedia dell’Arte, Humanist Commedia first, gradually followed by the Baroque and the Commedia in the Age of Enlightenment, is theatre. Pure, simply pure, theatre. It is the realm of the actor, there to serve his one and only master: the audience.

Antonio Fava - Biography

He directs the Scuola Internazionale dell’Attore Comico – SIAC (International School of the Comic Actor) in Reggio Emilia, Italy.

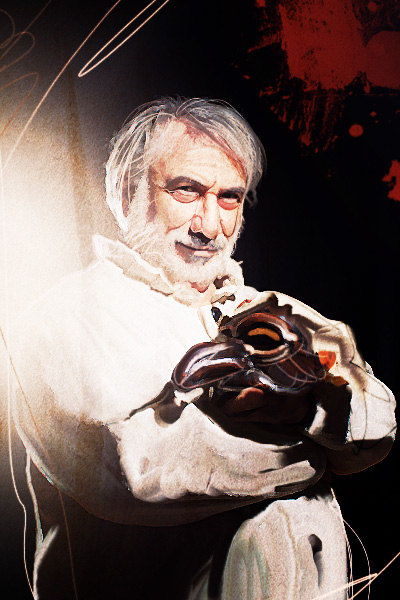

He designs and makes leather masks for use in his School and performances. He teaches Commedia dell’Arte in schools, universities and drama academies throughout the world.

His masks are on show in important museums and cultural institutions. He is an international director.

He is also author of the book entitled La Maschera Comica nella Commedia dell’Arte, published by Andromeda, English version, The Comic Mask in the Commedia dell’Arte, published by Northwestern University Press.

John Rudlin

The Routledge Companion to Commedia dell’Arte

AAVV

Routledge, London, 2015

I SERVI (THE SERVANTS)

ZANNI LUPO

Other interpretations of the origin of the name are forced or fantastical for example that one that makes Zanni derive from sannio, one of the Latin synonyms of histrio, buffoon, fool, comic.

In the speech of regions south of the Emilian-Tuscan Appennines, the name is clearly pronounced: Gianni and Gian, which are diminutives of Giovanni. The alpine-Paduan “Z” gives a dialectal pronunciation to the name but changes neither its roots nor its meaning. The name Zanni is the given name of a Commedia dell’Arte servant, historically the first of the Commedia characters, when it was performed with small groups of similar characters that were all similar in appearance, mask, behavior, and name. “Zan” was a sort of prefix before all their names, followed by the name that characterized the individual: Zan Salciccia, Zan Fritello, Zan Tabacco, and so on. Each actor invented his own.

With these characters, the first Commedia actors performed short, harsh comic stories of hunger, thievery, and fights in a shamelessly outlandish style, which they called zannate. The zannate, or zannesque comedies, staged by zanni actors,

By extension, used as a noun, zanni signifies a generic servant, the character of the servant in Commedia, any servant. The given name Zanni is thus used in plays when there is no more than one of the type, since no two Commedia characters can have the same name in a single story. The noun zanni is a technical term not used in performance. A master, for example, never calls for “his zanni”, but rather for “his servant”; if his servant happens to be named Zanni, then Pantalone calls for Zanni. An actor can play “a zanni” and this ‘zanni’ might be named Zanni or some other name. On stage therefore, we may have “many zanni”, who might be named Zanni, Brighella, Franceschina, Truffaldino, or Zan Trivella, Zan Farina, Zagna, Zan Tager, all interpreted by different actors, each a specialist in his own zanni.

PULCINELLA

Today, Pulcinella has perhaps too much history to be able to be described in a single way. Like Pirandello’s famous character, he is one, nobody, and a hundred thousand. Whoever he may be, he is always the comic symbol of the urgency of survival pure and simple. That’s what makes him stand for everyone; he couldn’t make it on his own.

I VECCHI (THE OLDS)

MAGNIFICO

DOTTOR PLUS QUAM PERFECTUS

A classic Bologna-dialect Doctor with multilinguistic layers. Great expert in everything, “Grand Old Man,” father of one of the two lovers, friend-enemy of Magnifico, with whom he is in eternal conflict-complicity.

This mask has the most reduced structure: just forehead and nose. The forehead is indispensable as a symbol of genius, the nose as the comic center of the face.

Doctor-like in everything, he is in reality a continuation of the ancient charlatan, who demonstrates spectacular but doubtful knowledge that depends on the ignorance of others – the other characters – which he can always count on, because they are indeed either more ignorant than he (servants, Capitano)

But he is truly, truly great in one thing: gastronomy. There, he excels. He goes into exaltation, he becomes deeply moved, he slobbers all over himself while describing the recipe, for instance, of the real lasagna, and he is scandalized, indignant, furious when reporting barbarous variations or ignoble practices.

The Doctor is the projection of the aspirations of an entire starving population that sees in him, in his immense gut, his fat pronunciation, his language that explosively re-invents all languages, and his intestinal outbursts, as overflowing as his gestures, the realization of their most gluttonous, prohibited internal desires.

I CAPITANI (LES CAPITAINS)

CAPITANO SPAVENTA

Il Capitano, in Commedia, è il guerriero, il bravaccio, il mercenario, l’uomo d’arme.

Gran combattente e grande amatore, è un eroe su ambo i fronti. Solitario, per motivi sia comico-poetici che funzionali. Fa coppia comica col suo servo, quando ce l’ha. È straniero, viene da lontano, ha visto tutto il mondo, vi ha visto cose che nessun altro può aver visto e vi ha fatto cose che nessun altro può aver fatto. Parla la sua lingua di straniero sospettosamente mescolata con quella del luogo (ossia, del pubblico). Naturalmente è un fanfarone, è il fanfarone per eccellenza; millantatore di straordinarie avventure, prodezze e prestazioni eroiche ed erotiche.

In realtà è un semplice ed un codardo. Ma questa terribile realtà, della quale lui ha vago ed inquieto sentore, va assolutamente tenuta nascosta. Esaspera la sua immagine virile e vincente per trarne vantaggi e soddisfazioni, ma forse soprattutto per nascondere l’intima verità, che lo fa soffrire terribilmente. È molto attuale, “nostro”, il Capitano. Ai tempi della Commedia storica tutti i suoi problemi relazionali si riassumevano in una parole: onore. Oggi la questione può apparirci risolta da parecchio tempo, ma non è cosí. Alcuni passaggi ci portano alla ridefinizione nostra: dall’onore al decoro, da questo alla dignità ed infine l’ “immagine”; è evidente che l’immagine ci concerne ed è altresí evidente che l’immagine è l’aggiornamento dell’onore. Il Capitano ha sempre avuto un problema di immagine. C’è dentro fino al collo in quel terribile problema.

Tutto il suo essere si muove nella direzione di dare di sé quell’immagine gloriosa e grandiosa senza la quale è finito, fallito, inesistente, morto. Ogni tentativo di imporre la sua immagine di sé costituisce un passo verso il disastro. Al suo primo apparire in scena il Capitano impressiona realmente gli altri personaggi, ma, ahilui, non regge la lunga durata e scivola fatalmente e rovinosamente verso la piú fangosa vergogna, fino alle legnate ed alla fuga finali. L’interprete del Capitano fornisce immediatamente al pubblico tutti i segnali comici che significano il destino del personaggio.

Il Capitano non ha cultura, ma ha orecchio, cosí che una narrazione “da bar” si arricchisce di citazioni (dubbie) e di riferimenti culturali (incerti), preferibilmente di carattere mitologico. Il Capitano che ‘fa una bravura’ è un bellissimo esempio di teatro pensato per tutto il pubblico, tutti i livelli di comprensione e gradimento. Infatti la sua dimensione di eroe da taverna lo avvicina al pubblico equivalente, ma i contenuti di cultura sapientemente “orecchiata”, alzano via via il livello, fino ad imporsi ai palati piú fini. In questo senso, il Capitano è come dovrebbe essere – a nostro avviso – il teatro, tutto il teatro: chiaro, popolare (ossia, per tutti), divertente, raffinato; ed anche “problematico”, come lo è il Capitano.

Il Grande Affabulatore ha dunque questa dimensione dalla sua; ma anche un’altra: è un grande amatore. L’animale uomo di sesso maschile non falla. Delle sue doti amatorie ne gioisce – oltre a lui stesso – soprattutto la sua referente ed equivalente femminile, la Seconda Donna, o Signora, giovane, bella, spavalda, fanfarona come lui (ma non codarda, anzi, piuttosto aggressiva), moglie dell’irrimediabilmente, costituzionalmente cornuto Magnifico, oppure (che è lo stesso) Dottore. Va da sé che la Signora, sposando un vecchio, ha sposato il suo capitale, che ama tanto e del quale ostenta gli effetto, sviluppando lei il tema dello status con egual poetica e tematica del capitano in rapporto all’eroismo: entrambi hanno un problema di immagine.

Con la sua funzione di “intruso”, di “terzo incomodo”, il Capitano si porta addosso il marchio della colpevolezza ed il destino dello “smascheramento”. Si riavrà dallo svergognamento e dalla bastonatura finali quel tanto che basta per preparare un’uscita di scena durante la quale darà fondo alla sua mitomania che gli farà immaginare, terapeuticamente, un futuro di ben piú grandi glorie e trionfi.

MASCHERE SOCIALI

ANDROGYNE

I SATIRI

SATIRO GRAN CORNUTO

Il Satiro “gran cornuto” è cosí chiamato per evidentissime ragioni.

Nel nostro lavoro, in allestimenti come nella scuola di teatro comico, le maschere dei satiri vengono studiate come esseri significanti le forze della natura ed agenti sempre e comunque: anche lo stato di immobilità rimanda a certi immobilismi sia naturali che sociali, coi quali i personaggi si trovano a dover fare i conti.

Il nostro satiro non parla, ma emette suoni molto espressivi e significativi.

THE COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE

A genre that does not deviate from its nature, the theatrical one: Commedia dell’Arte is Theatre; as a profession, which has been since its very early days , it does require a certain degree of organisation and it does organise everything: the Acting Company, every single Specialization (Fixed Types), the dramaturgical structure, which has not changed for centuries,

Commedia dell’Arte talks about real people in real situations in a very spectacular manner: it is the Big Show of the collective truth, of us all.

By Commedia dell’Arte we usually mean comedy.However, ’Commedia dell’Arte’ is rather a summarising expression of a production system that combines different genres: comedy and poetry as in the Pastoral Comedy, in the Boschereccia, Marinaresca and Piscatoria ones; epic in Opera Eroica; tragedy in Opera Regia.